Why Are Older Adults Working Longer?

Why are older adults working longer?

By Sam Deleo

Tucker Advisors Senior Content Specialist/Editor

We are about to experience a major transformation of our labor force in the United States. Is it the change we want?

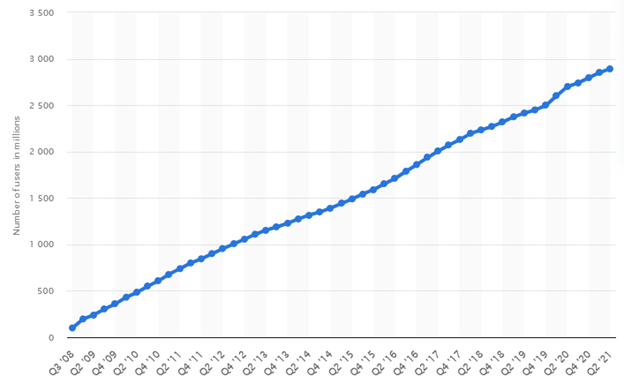

Forty years ago, the federal government lengthened Social Security’s full retirement age (FRA) from 65 to 67, and increased the delayed retirement credit. This incentivized people to work longer and, in fact, the U.S. Bureau of Labor’s statistics show this is exactly what many Americans began to do.

Since 1983, employment rates for men aged 65-69 have risen by 10%, and by 15% for women in the same age group. By next year, 2024, one in four workers will be 55 or older, which is an over 100% increase from 30 years ago in 1994.

But the Bureau of Labor data shows that something else has also occurred over the last four decades: People lost their pensions (defined benefit plans) and were forced into defined contribution plans, usually in the form of 401(k)s. Since 1980 through 2014, workers with retirement plans that included a pension fell from 39% to 13%, a 200% decline. Conversely, workers who only have 401(k)s or defined contribution plans, rose from 9 to 34%. The Bureau of Labor has coined this loss of pensions as a “negative wealth effect” that has caused workers to be “increasingly motivated to work past the FRA.”

Some of us tend to leave these statistics out of the discussion when pointing to increased longevity and health, or even boredom, as reasons that older adults are working longer. And yet, it’s true that there can be many advantages to working past traditional retirement ages that contribute to a better quality of life, as well as more robust financial portfolios.

Older, not lesser

While ageism may unfortunately be the last-standing, socially tolerable form of discrimination, older workers are shattering its stereotypes. Senior employees tend to promote positive “can-do” attitudes in the workplace. The American Association of Retired Persons (AARP) reported that workers over 55 performed with the highest levels of positive engagement in the workplace. Their survey also showed that younger employees viewed their older colleagues as teachers of on-the-job skills. In a study from 2021, the Department of Labor found that older workers could save employers money on re-training costs because they tended to remain more loyal to remaining with the company than younger workers.

Those who decide to work past the traditional retirement age of 65 can help deter the development of dementia, avoid feelings of isolation if they are widowed or alone, and consistently maintain an active lifestyle. A study in the Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health found that working even just one year past 65 can increase one’s lifespan by 11%.

“A huge part of our self-worth is attached to work,” said Bryce Gill, an economist with the investment firm First Trust. “So it’s not surprising some people want to continue working if they can.” Gill points out that the bigger factor may be that the nature of work has changed over the last century to allow people to consider the option to extending their employment: “It’s no longer the case that a majority of people are performing physical labor, which made it impossible for older adults to work many of those jobs in their later years.”

“I think that the research now bears out that people’s health outcomes and longevity both increase when they work longer,” said Bridget Sullivan Mermel, CFP®, CPA, host of “The Chicago Money Show” and the YouTube channel, “Friends Talk Financial Planning.” “From a health standpoint, it keeps you active, but it also gives you a sense of purpose. So, when discussing older adults working longer, the ideal scenario is a job in the last 10 years of their working careers that is not too stressful or taxing physically.”

In terms of personal finances, those who decide to work longer experience nearly exponentially compounded gains. Not only are they able to allow their savings to accrue more interest for a longer period of time before drawing from them, but they can often shift into a lower tax bracket and supplement their financial portfolios.

“Every year you work longer, you’re giving yourself more options,” said Sullivan Mermel, “you’re getting away from poverty-level income in retirement.” But it’s important that people optimize the money they earn. Paying off credit cards is not a sound reason to delay retirement. In one manifestation or another, people should be contributing to their savings. “You can both pay off debt and save,” said Sullivan Mermel, “but never do away with the latter in favor of the former, or in hopes you’ll begin saving sometime in the future. If you’re going to work longer, you have to get out of this paycheck-to-paycheck thinking habit. Otherwise, you may just be perpetuating an endless cycle and never be able to stop working.”

Why not retire?

The sheer scale of people working past 65 warrants a closer look into the reasons why. Referenced in a 2022 study by Voya Cares, the Bureau of Labor predicts the trend of older adults working longer to keep accelerating. About one of every three people (32%) between the ages of 65 to 74 is expected to be to be working in 2030, as opposed with 27% in 2020 and 19% in 2000. For those 75 and older, the bureau projects 12 percent to be working in 2030, compared with only 5 percent in 2000 and 9 percent in 2020. But the study also dug a bit deeper than other surveys on this topic:

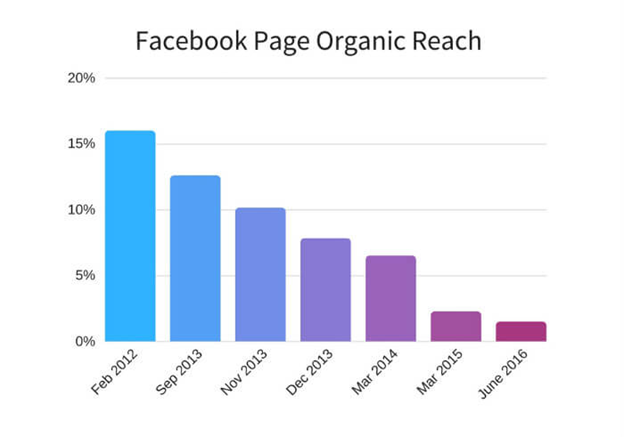

Statistics may show that older Americans are working longer. But, as working past FRA transitions into more of the norm in America, people also appear to be losing hope in the possibility of reaching retirement, in choosing not to work. Recent studies by YouGov.com echo the responses in the Voya Cares report:

These figures do not cancel the positives of working longer. But they do place them in a different context.

“In general, when it comes to finance and economics, we tend to discuss everything as choice or options,” said Tanja Hester, author of “Work Optional: Retire Early the Non-Penny-Pinching Way.” “That is not always the case for a large number of people. The amount often cited for what people have saved for retirement is slightly above $140,000. But that number is an average—the median would be lower, and the modal would be much, much lower. The largest number of Americans have zero saved for retirement.”

Have we become a nation living paycheck to paycheck?

CNBC recently cited a survey by Vanguard titled, “How America Saves 2022,” which supports Hester’s comments. According to the study, people have saved an average of $141,542 for retirement, but the median account balance was only $35,345, which means half of the accounts were above this number and half were below. This median figure provides a bit truer picture by canceling the outliers that can distort the average amount.

As a consumer society, we have never placed an emphasis on saving money. But wages have also not kept up with inflation and the cost of living over the last several decades. From 1979 to 2018, wages rose five times less than productivity. The current inflation rate of 6% has only made saving more difficult.

“You need to be responsible,” said Gill. “On the other hand, we know that 80 percent of stocks are owned by wealthier people. How do we change that so people can choose not to keep working if that’s what they would like to do?”

recapturing choice

Besides inherited wealth, stock ownership has traditionally been a central means to accumulating revenue in the U.S. Far too many people have overlooked it as an alternative because they either felt they did not have enough money to invest or could not seem to consistently budget money for the purpose of investing. Defined contribution plans like 401(k)s have helped to offer people some exposure in the market, where they can generate savings.

“My first job out of college in my early 20s, I remember maxing out my 401(k),” said Gill. “And the number of people at my job who were contributing nothing, even to the matching amount—which is free money—must have been in the majority, which was absolutely shocking to me.”

If workers still have available income to dedicate after investing in their defined contribution plans, they can consider stocks, but only with a full understanding of the risk. “You should have a bare minimum of $10,000 to $20,000 in mutual or indexed funds before even considering looking at an individual stock,” said Gill. “I’m a financial analyst, but even I am not going to succeed with individual stocks more than about one third of the time. Investing is not sexy. I recommend sticking with index funds and avoiding individual stocks. The easiest and most productive habit can be to set up a regular contribution schedule to something like a Vanguard Index fund.”

Money matters are emotional because they permeate our personal relationships. This is why they demand our careful attention, and delaying them in favor of a more convenient time in the future to deal with them is often a vicious cycle for many of us. We owe it to ourselves to act as preventively with our money as we do with our health issues.

“When my husband and I met and merged our accounts, our first paycheck would go to rent and our second paycheck automatically got deposited into our investment accounts,” said Hester. “The biggest difference-maker for me involves creating automated plans. We all have limited willpower, and we all have limited means of using it every day. So, to expect people to put aside money on a regular basis is asking a lot. If you have a workplace retirement account, automatic contributions help. Also, escalator options exist for these contributions when people get raises or COLA increases. But, if you don’t have those savings options, you can still split your bank accounts and have some of your paychecks automatically deposit into your savings account. I started with $50 in my savings account when I was in my 20s. It doesn’t sound like a lot, and it isn’t. But it added up. So, find banks that allow paycheck splits.”

The reason automation can be so critical to saving for retirement involves human nature—it’s easier not to plan than it is to plan. If we have scheduled automatic contributions to our retirement savings, we can choose a number of budget adjustments to make up for that missing money. However, if we rely on finding the money each month among our other expenses, without an automated plan, we’re less likely to make the contributions.

Some financial planners have suggested that an automatic opt-in to a retirement contribution plan like a 401(k) should be the default when employees are hired, giving them the choice to opt out if they choose to, rather than vice versa, as these plans are set up now. This could allow people to get used to budget adjustments from the very start of their new job and wages.

“Automatic opt-in is one way of trying to avoid underfunded retirement savings, because we don’t always think in our best interests,” said Sullivan Mermel. “As for opt-in savings plans, if we’re going to do it, I want it to be a healthy percentage, I want people to have money in these accounts. Let’s not bother with just 3%, because then, what’s the point?”

Sullivan Mermel recommends that auto deductions be a topic of conversation for financial advisors with their prospects and clients. “Try to figure out what might be interesting to them—if it’s stocks, great, that’s fine,” she said. “You’re still encouraging them to take that money out of their paycheck-to-paycheck cycle of expenses.”

Reversing the trend in deficit retirement savings can, and often should, involve people seeking out professional financial planning advice. Most financial advisors offer free consultations and can at least offer people the broad details of a financial plan. But many older adults have never taken advantage of this opportunity. Consequently, they budget their money without a financial plan to direct their savings actions.

In order to enjoy the maximum benefits of meeting with a financial planner, timing is key. Waiting until 63 to plan for a retirement at 65 is not a sound strategy. The earlier people meet with financial advisors, the more the advisors can do to mitigate savings deficits.

“I want to meet with someone five years minimum before they want to retire,” said Sullivan Mermel, “so I can implement tax strategies alongside investment strategies and have them both work in unison.”

As one of the founding figures in the “financial independence, retire early” (F.I.R.E.) movement, Hester mentioned some less conventional ways people can prepare for retirement, such as health care subsidies in states that have expanded Medicaid. “These are called ‘advanced premium tax credits,’ “ said Hester, “and they are means-tested and based on income, not assets. If your health insurance could basically become free, that eliminates a huge expense for people.”

For those who live in mid-range to high-cost areas, moving to a low-cost state can sometimes add to their savings, Hester said. But it’s critical to thoroughly research all the costs involved, some of which may not be obvious, such as housing codes, property taxes, state taxes, etc. Some retirement experts even advise visiting a proposed change of location at different seasons of the year to better gauge expenses.

“It’s important to have the traditional diversified portfolio plan,” said Hester. “But also include contingency accounts, like a high-yield savings instrument, an income property that you can rent as long as you are able to and then sell in retirement if necessary, or an inheritance, even small, placed in a growth account. Mortgage payoffs also can work this way to generate retirement money.”

Everyone has their own unique set of financial circumstances, and so they will have slightly different solutions to their paths to retirement. Many financial advisors, for instance, might recommend rolling over 401(k)s to Roth IRAs as a savings strategy, but Hester said even that common practice deserves scrutiny. “Research the cost basis for traditional IRAs, because dividends and capital gains are taxed at a lower rate, so it may be better, unless you’re wealthy, to keep a traditional IRA. Tax avoidance at all costs is not right for everyone.”

what future do we want for ourselves?

Can we celebrate a sense of purpose in the jobs we work as older adults? Is it healthier to age working or playing? Do we want to spend our later years more with our co-workers or our grandchildren?

The world of work is changing rapidly around us in ways that people could not have foreseen 40 years ago. These changes deliver a range of advantages and disadvantages to older workers, as well as new challenges. How will we decide to meet these challenges?

When it comes to Social Security, for instance, there are those who favor a path to privatization and those who would rather expand the public program that already exists. Referenced by CBS News, a Congressional Budget Office (CBO) study last December showed that doing away with Social Security’s $160,200 tax cap in favor of eliminating the cap for earnings over $250,000 would fund the program through 2046.

If 65 is no longer a reasonable age to retire, what age is? Some members of Congress have rightly pointed out that most Americans are living longer than they were decades ago and can safely work until 70. The CBO’s study found that raising full retirement age to 70, however, would effectively cut benefits for today’s current workers, costing them each an average of $65,000 in payments.

Perhaps there are no absolutes when it comes to private or public solutions for our retirement deficits. People need to act more responsibly in converting their earnings into savings. And we as a society may have to consider options like revising our defined contribution plans, which may require greater responsibility from employers or new legislation from Congress.

“People need to have a financial plan at least 10 years out from the time they want to retire, if not longer,” said Sullivan Mermel. “Maybe a default contribution or some other revision to 401(k)s is the lesser of two evils when compared to dramatically increasing Social Security or administering some other bailout for older adults, which everyone ends up having to pay for in the end.”

None of our options will be easy, and no consensus of opinion will ever likely be reached. But if we want to keep alive our choice to retire, we can no longer wait to act.

9. YouGov.com

Join Tucker Advisors

Call 720-702-8811 or email COO Jason Lechuga at Jason.Lechuga@TuckerAdvisors.com